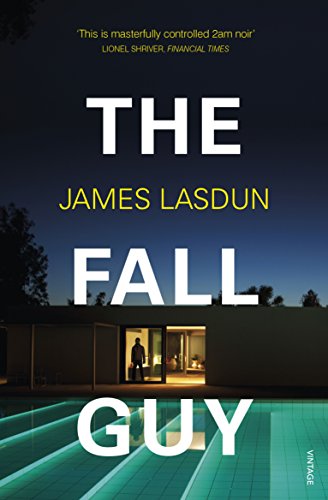

And did I mention it’s got a great, gripping plot?

Last week, I read it for the third time since its publication. And it still held my attention.

Matthew, a struggling chef who hasn't had a regular job in a couple of years, is invited to spend Summer 2012 at the guest house of his cousin Charlie's summer home in the Catskills. When they were younger, after Charlie's father died, Charlie had moved into Matthew's family home in London. They went to a posh private school together, lived as brothers. But now the tables are reversed. Matthew is the down-and-out hanger-oner. Charles is a wealthy banker, the type of guy who keeps $1.5 million in cash in his home safe.

Almost immediately, we sense a simmering animosity between Charlie and Matthew. And almost immediately, we sense Matthew’s attraction to Chloe, Charlie’s wife.

One night, owing to a strange sense of circumstances, Matthew’s sleeping in the bedroom of Charlie and Chloe’s vacant house.

“As [Matthew] laid his head on the pillow, he caught the smell of Chloe’s perfume. He breathed it in deeply. As always, it stirred a very specific emotion inside him; unnameable, but powerfully evocative of it’s wearer. A short, sheer nightdress with thin shoulder straps lay crumpled on the carpet below the mattress. He picked it up and held it against the light. A strand of Chloe’s dark hair glinted on the cream-colored silk. He let the garment slide down softly against his cheek, and filled his lungs again with the delicately scented fragrance.”

Ultimately, this is a novel about betrayal... and yet, it's not the obvious betrayal that fuels this novel's tension. Matthew spends his days cooking up fantastic meals for Charlie & Chloe, all the while working up the gumption to ask Charlie for $50,000 to start a gourmet food truck business. Chloe spends her days swimming and going to yoga classes. And Charlie meditates, adopts leftsy yearnings (he's sympathetic to then-current Occupy Wall Street movement) and plots a new microfinancing business venture.

The problems really begin when a fourth character enters the narrative about fifty pages into this novel. From there on out, the tension's fantastic. Each of the characters is caught in their own obsession.

One of the things I really liked about this novel is the writing-- it's superb.

And I also relished how the main story arc emerges slowly but then becomes all-consuming. This is not a typical mass-market psychological thriller. Yes, there are twists and double-crosses that I never saw coming, but I sense that Lasdun had more than just an entertaining twist or two when he began writing this novel. He pays particularly close attention to the political currents that infused the summer of 2012. All the characters, to some degree, are ostensibly trying to break out of their socioeconomic stereotype. And yet, as much as they'd like to be freed of their predicaments, none of them wholly succeed in becoming something other than the person they were at the beginning of the novel.

*****

In the past, I’ve been lucky to interview several psychological thriller writers (including Mary Kubica, Lisa Jewell, and Anna Snoestra, and Kaira Rouda). James Lasdun has kindly consented to answer a few questions via email about his novel, THE FALL GUY.

Question: Typically, in what might be called ‘commercial’ psychological thrillers, there’s an emphasis on plot elements. However, THE FALL GUY also features an intense focus on character, place, socioeconomic zeitgeist, language, and, of course, its sizzling plot. How do you balance these many elements? Do you find that, at times, prioritizing on or another of these non-plot elements can detract from readers’ immersion in the plot?

James Lasdun:

I have huge respect for plot, regardless of genre, and I do think that, ideally, everything that happens in a novel ought to advance the plot in some way. Of course you want to make the characters and places as rich and vivid as possible, and maybe even give yourself room to explore some ideas, but – for me – if those things aren’t subordinated to the story, then you’re in trouble. That said, I think my idea of what constitutes ‘story’ may not be typical for a thriller writer. I find I need to chart characters’ states of mind in some detail as the psychological pressures mount, and this can sometimes involve fuller explorations of the worlds they inhabit than other thriller writers would allow themselves. For me, part of the pleasure of writing (and reading) this kind of book is finding believable situations that can express the different phases of a deepening crisis, while simultaneously developing a realistic portrait of a particular world.

Question: Unlike a lot of psychological thrillers—which open with a death, a confrontation, or crucial revelation—THE FALL GOES doesn’t start in a stressful place but slowly eases into the story.

Two cousins, Matthew and Charlie, meet and drive upstate “late so as to avoid the traffic.”

There’s a disparity between Charlie and Matthew. Charlie’s an incredibly wealthy banker. Matthew however, is only marginally employed and hemmed in by dwindling financial resources. One senses quickly that grudges animate Matthew.

The opening pages do an excellent job in establishing the relationship between the principle characters. We get to know the town where, along with Charlie’s wife Chloe, the three will be summering. And we get to understand the novel’s themes and ideas (more about this later) but in positioning THE FALL GUY as a psychological thriller, was there a moment when you and/or your editors were tempted to start the novel with a sensational event that would immediately activate the plot’s forward momentum?

James Lasdun:

This may just be a matter of personal taste. I like simple, low-key openings that bring the world of the book calmly to life, and set its basic psychological conflicts in motion in a very natural and plausible way. Of course you have to cast a spell in some way from the first page, but I don’t think that has to involve some big sensational event (I don’t much like being grabbed by the throat). For me it was enough just to travel for a bit with these two cousins whose relationship has a serious power imbalance in it that is clearly (I hope!) going to lead to some kind of catastrophe, especially when we learn of Matthew’s very specific feelings about Charlie’s wife.

Question: A similar question: about 50 pages into the novel, Matthew witnesses an incident. A secret is revealed will unravel the cozy if carefully-boundaried relationships between the characters.

My question has to do with pacing. This is the moment the plot engine kicks fully into gear. For me, the timing of this moment seemed perfect. And yet this is exactly the kind of “sensational moment” that other writers might wish to craft as into an opening chapter. Were you tempted to do so?

James Lasdun:

My hope was that there was enough tension inherent in the Matthew/Charlie/Chloe situation, along with the money story, to keep things interesting and build a genuine sense of suspense. It was important to me to create the sense of a desirable, even blissful existence making itself available to Matthew. He can’t have it, but it exists around him as a tantalizing possibility, which – to me – gives meaning to his destructive, self-destructive unraveling. But I take your point about pacing – it was risky to hold back on some of the key disclosures for as long as I did.

[Nick Kocz Addendum: In this case, the risk was well worth it! I’ve been re-reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels and short stories over the last week in anticipation of writing an essay about why I never want my 17-year-old son to be as steeped in Fitzgerald’s work as I was at his age. One of the things that drew me in to both THE FALLL GUY and THE GREAT GATSBY is the relative slow build that Lasdun and Fitzgerald employ. Absent of heavy-handed sensational plot moves, the slow build forces readers to “lean in” more, and pay greater attention to non-plot elements.]

Question: THE FALL GUY is a cauldron of opposing forces and churning, burbling ideas all in conflict with one another. When tasked to select music for their drive upstate, programs, Matthew programs the Lexus’s iPod to play Debussy’s piano compositions-- a choice Charlie vetoes in favor of Plan B’s “hard beats and aggressive voices” hip hop.

Charlie, the banker whose favorite beverage is watermelon juice, studies the Occupy Wall Street protesters of the early 2010s, searching their faces for signs of “authenticity.” Although his past isn’t squeaky clean, he now seeks to set himself up as a financial ethics consultant.

Aurelia, the Woodstock, NY-like town where the novel is set, began as a 19th century artists colony and is now home to “an unusual combination of ragged drifters and well-heeled New York weekenders who mingled together in a curious symbiosis of mutual flattery.” One of the characters aims to write “a more cultural-historical sort of book I’m thinking of calling The Last Taboo, about money—how it affects the consciousness of people who have it, or work with it.”

Deadheads and hippie counter-culture nomads bivouac in the surrounding woods and lay among the flat rocks of the town’s stream, where their leaders break apart baguettes to share among their followers.

THE FALL GUY contains one of the most perfect images I’ve read in ages, something that stuck to me in each of my repeated readings of the novel:

“The small trees flanking the path, sentinel-like presences in last night’s darkness, turned out to be dwarf pear trees, laden with small green fruit. A faux-bronze Buddha, Aurelia’s ubiquitous totem, sat in the shade of a maple, smiling. The peacefulness of the place was a little uncanny.”

The peace is, indeed, uncanny.

And yet, as logical readers, we sense unease. Conflicting interests can not peacefully co-exist for long before something explodes.

What I’m getting at is that, as much as THE FALL GUY rightly qualifies as a “psychological thriller,” it could also be labeled as a “sociological thriller” or a “socioeconomic thriller.” How important was this overarching aspect of the novel to you compared to the personal dramas affecting each of the individual characters?

James Lasdun:

Well, place and politics are both important to me. I don’t think I could write a book that didn’t explore both in some way. Certainly both were integral to the story from the beginning. I like your term “socioeconomic thriller” though I hope the book has an equally prominent psychological/emotional aspect too. The banking collapse was very much in my mind when I was first thinking about the story. I wanted a banker to be one of the main characters partly in order to connect the story directly to that subject. The idea of a remorseful banker trying to atone for the sins of his profession, while being still completely in the grip of the mindset underlying those sins, interested me. I hope the question of culpability (and the evasion thereof), which is really the driving idea of the book, gets some resonance from this political context. Of course it needs to work on the personal level first, so the human relationships have to be believable…

Question: Often, when reading commercial psychological thrillers, I get the feeling they’re written with the assumption that readers demand each scene/page/paragraph/line in some way directly services the plot. You don’t seem to be under any such assumption. Why?

My take on THE FALL GUY is that it’s an intelligent corrective for what, at times, feels like a lazy commercial genre trafficking in tropes and quick plot moves rather than intelligent observation. THE FALL GUY takes risks. Not all the scenes are in direct service to the plot. There’s a long dinner party scene about one-third through the novel, for example, that serves thematic rather than plot needs. Matthew, a foodie who’d rather “go to bed hungry than eat poorly” introduces readers to an abundance of mouth-watering food observations during his numerous marketing trips.

In your estimation, what are the advantages to your strategy? And what, if any, disadvantages might there be?

James Lasdun:

Nice of you to say, though in fact, as per question#1, I do think every scene should serve some plot need – it’s just that the ‘plot’ sometimes goes inward or underground, in the sense of being more about shifts in a character’s psyche or perception of things, than concrete action. In my mind that dinner party scene, while of course offering an opportunity to bring in more characters and air some of the book’s themes in the form of direct conversation (and with luck provide some light relief!), is primarily geared around a critical shift in the way Matthew views his relationship with Charlie. It’s the first time he senses direct, unequivocal antagonism from Charlie, and it also sets up a scene that gets replayed from a very different perspective when he hears Chloe describing it to Wade. It becomes (if it works) a way of expressing the extreme subjectivity of Matthew’s view of his own behavior. I wanted him to seem both more oppressed and more dangerous as the story evolves. A lot of the more seemingly low-key moments and scenes represent my attempts to get inside his mental processes sufficiently clearly that I could really believe he would commit an act of violence when the moment came. The food descriptions, which get more elaborate (and less appetizing) as the story progresses, are also a part of this attempt to find ways of charting Matthew’s darkening state of mind. (I wanted them to be fun too, though).

Question: How did the THE FALL GUY develop in your mind? Did the plot come to you first? Or did you begin with a character sketch or scene? Or the atmospherics and social dynamics? How long did it take before all the elements finally came together in your mind?

James Lasdun:

I think three things came together. First, the configuration of characters; basically a triangle that gets unexpectedly turned into a foursome. I hadn’t seen this particular dynamic of desires and resentments before, and it intrigued me. Then all the politics around Occupy, etcetera, that was still so much in the air when I started writing. And then just my own longstanding wish to capture the feel of summer in the Catskills, where I live. Somehow this dark story seemed to go well with that bucolic setting. The writing was pretty quick by my standards – about a year for most of it, then several more months trying to get an ending that satisfied me and my (very exacting!) editors.

Question: Which contemporary writers of psychological thrillers interest you most nowadays? What recent novels have you found especially noteworthy?

James Lasdun:

I enjoyed Leila Slimani’s “The Nanny”, though maybe more for its subtler moments of human observation in the first half, than the build-up to its gory climax. I also very much admire Lawrence Osborne’s novels, which use place and atmosphere brilliantly, as well as being just highly intelligent about the world we all inhabit.

Question: Weeks ago, I read through the Amazon reviews for my first novel (I WILL NEVER LEAVE YOU), which had just been published. This was an eye-opening experience. I expected readers to comment on style and tone, imagery and themes, and the quality of writing at the sentence-level. In short, I expected them to comment on the qualities that I admire in THE FALL GUY. Instead, readers focused on plot, pacing, and character likability issues. What do you hope or expect your readers to walk away with after reading one of your novels?

James Lasdun:

I think it’s dangerous for writers to try to tailor their books toward some sense of what ‘the reader’ might want. Also dangerous to read Amazon reviews! You can’t write a good book by second-guessing reader responses, though I suppose if you’re clever at it you might write a successful one. I write to please myself, and hope in doing to give pleasure to other people. I try to make my sentences as clear and expressive as I can, but I don’t particularly care if anyone notices. It’s nice if they do, but that isn’t the reason why most people (other than writers of course!) read thrillers. They want to be saturated in anxiety and terror and then released from it. For that to happen (for me) the writing has to be alive, intelligent, attentive to reality, otherwise I get bored and stop suspending disbelief. But at the same time I don’t like to be too conscious of an author’s style, imagery, etcetera. It’s a difficult balance to strike… At any rate I’d rather my novels left readers with a sense of having been on a rich, strange, deep, dark journey, than filled with aesthetic admiration for the prose.

Addendum: I WILL NEVER LEAVE YOU, written under the pen name of S. M. Thayer, actually continues to perform very well. For several days, it was actually the best-selling novel of any kind at Amazon. A couple of weeks ago, it was #12 on the Washington Post’s National Fiction Best-Seller’s list. Although it’s been available since August 1 as part of Amazon’s First Reads program, its technical publication date is September 1. It’s been strange a strange experience for me. Several readers have reached out to me out of the blue, telling me how much they enjoyed the novel. As you might gather, until this moment I’ve had little to no experience responding to fan mail. But I can’t tell you how grateful I am to everyone who’s chosen to read my novel. Thank you!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed