Counting summer conferences, community workshops, and grad school, I’ve now taken twelve fiction workshops. Of these, Frank’s was the most brutal. None of the eight or ten of us taking the workshop wrote especially well, as we repeatedly reminded each other. Nor were we delicate in pointing out each other’s failings. We were not a good community. Several times, people left in tears.

Frank was not adverse to letting us beat up on each other.

Amid such cruelty, Frank performed an incredible act of kindness.

My first workshop story was 52-pages long. I had labored over it during a long weekend, stuffing it chockfull of allegory and literary allusions and foreshadowing and incredibly philosophical yet witty dialogue. I thought it was brilliant.

Of the stories that were to be workshopped that afternoon, mine was to go last. We spent an inordinately long time discussing the other stories. Every few minutes, Frank would fling out his arm, look at his wristwatch, and go back to discussing those stories.

At the end of class, he flung out his arm again and winced. He turned to me. “I’m sorry. It looks like I didn’t budget enough time to get to your story. Why don’t you come back to my office and we’ll talk about it.”

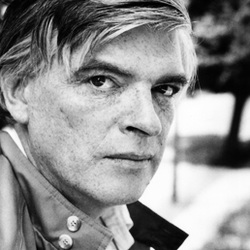

I don’t recall much about his office, other than it was in a state of disarray. Books and papers spilled out over his desk. An ashtray sat in one corner, overflowing. Because I was young and stupid, I thought he was going to praise my story. He had told us about his New Yorker editors and the office he shared with Norman Mailer, how the two of them would lunch at The Automat together. I thought he was going to suggest I send it to an agent or another of his literary connections.

We made small talk for several minutes. I asked what he thought of my story.

He lit another cigarette. “Well, I could tell that you read a lot.”

This small compliment inflated me greatly. “And?”

When Frank smiled, which he did whenever he wanted to let you know he meant no harm, he could appear downright boyish. “Don’t try so hard, okay? Just do what you’re capable of doing.”

Years later, I realized that had he formally workshopped that story, I would have been scarred for life. That story was called “Somewhere They Care.” I could only imagine how the workshop would have torn it apart—and rightfully so: it was wretched. Talking with me in private allowed me to escape with my dignity intact.

As a workshop leader, Frank was a mixed bag. He did nothing to curtail our nastiness towards each other. While I can’t recall him actually belittling our writing, the fact that he did not rein us in probably encouraged further nastiness. Constructive criticism and thoughtful discussion, two aims of any workshop, did not have a chance in that poisoned environment.

I’m still appalled at how nasty that workshop was. I struggle to understand why he did not create a more positive environment. I remember what Flannery O’Connor once wrote:

“Everywhere I go, I'm asked if the universities stifle writers. My opinion is that they don't stifle enough of them.”

The only thing I can think is that Frank bought Flannery’s tough-love approach.

Yet, strange as this sounds, we all trusted him implicitly with our writing. We were naïve and he was probably the only New Yorker writer that any of us knew.

Frank’s workshop was also unique on one other count: all the focus was aimed at the sentence- and word- level. To Frank, sentences were like mathematical proofs: if everything added up right, you’d end up with a clear sense of meaning. We’d read our sentences aloud, pin-pointing where meaning became fuzzy due to poor constructions or word choice. Many of us (me included) wanted to believe that imprecise sentences were worth retaining because however poorly written, readers would still understand the gist of their intended meaning. Frank disabused us of that notion. He would not cotton to figurative language. Or especially fancy language. What he strove for were clean, crisp sentences.

I say this was unusual not because my other teachers were fond of imprecise language, but because the focus in those other workshops usually was on more global issues like story structure and character motivation.

Sometimes, in those other workshops, we’d look at stories that were so “hastily” (hastily: a euphemism meaning “poorly”) written that one would be hard-pressed to say exactly what happened in them. Instead of discussing the prose, we’d have half-hour discussions about why character X would or wouldn’t do a particular something. Or we’d talk about why an ending just wasn’t satisfying.

The impulse to withhold comment on glaringly bad prose stems from a desire not to offend fellow writers. Criticism about improper character motivation is easier to stomach than being told that your writing is bad. Spared of this nice-nice ethic as we were in Frank’s workshop, we’d rip savagely into each other’s prose.

Misguided as it sounds, I’d like to think that Frank's focus on prose helped me. I was so new to writing that talk about story structure and plot points would have been of no immediate use.

The other three stories I wrote that semester were shorter, more concentrated—the longest might have been twelve pages. The last of those was actually one of the few workshop stories that semester which Frank actually liked—well, “like” might be too strong of a word. The workshop was so dysfunctional that when he praised a couple of my lines, other workshoppers tried to convince him that his praise was misplaced. How’s that for nasty?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed