A couple of days ago, I caught a podcast of J. Robert Lennon interviewing Nicholson Baker. Besides writing some of my favorite novels (Mezzanine, A Box of Matches, The Anthologist), Baker’s also writes thoughtfully on text preservation and the effects of technology on the written word. Recall, for example, his 2009 New Yorker article on the Kindle.

Baker seems to be more comfortable with e-readers nowadays, yet he still “connect[s] better with a printed book.”

“[T]here’s somehow a kind of connection that the text [provides]… There’s a more complete experience. I remember it more. I come away with more. I don’t know if it’s just my own [experience], you know, just because I grew up in a paper-based world or something, but it’s still true for me.”

So it looks like Baker’s not getting total immersion from his e-reader.

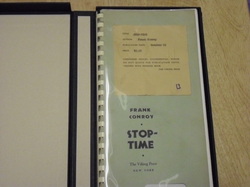

I’m not a rare book collector, but over the years I’ve picked up a few rare items. Sixteen years ago, I came across a set of uncorrected galleys to Frank Conroy’s Stop-Time. Conroy, as I wrote recently, was my first creative writing teacher, so the galleys to his masterpiece have personal meaning to me.

The galleys were previously owned by Carter Burden, the one-time publisher of The Village Voice who had amassed one of the finest collection of twentieth-century US first editions. To house the galleys, Burden had a special case made.

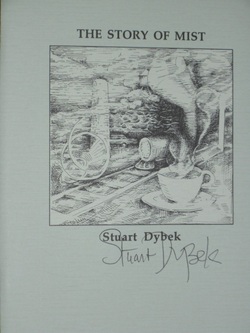

A few years after I bought the chapbook, Dybek came to Washington as part of the Pen Faulkner reading series. ZZ Packer was also reading on the same bill. Afterwards, lines formed so that audience members could meet the writers. Dybek looked startled when he saw I wanted him to sign my copy of his chapbook. Most people were asking him to sign copies of his then-current collection, I Sailed with Magellan—and here I was with some obscure chapbook that had been issued more than a decade prior. Dybek seemed wary. I sensed he feared I was some kind of fanatic—a mad fan who might attempt to chat him up for hours or even stalk him after the event. It was awkward. He had been friendly with almost everyone else in line, laughing and telling jokes. With me, silence.

That same night, my wife and I talked with ZZ Packer for maybe five minutes. She was charming, totally at ease with all the attention she was receiving for her collection, Drinking Coffee Elsewhere, which we had her sign for us.

Still, despite that experience, I'll always treasure my copy of The Story of Mist.

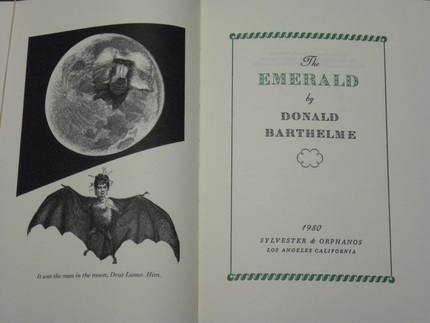

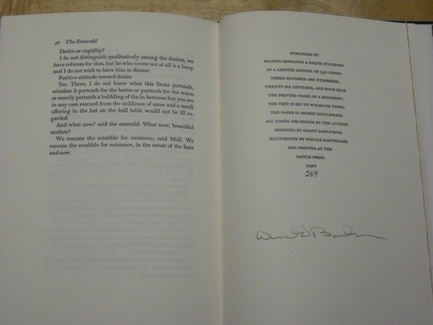

This book is just so beautifully printed and bound. What pictures I’ve snapped just cannot do it justice.

However…yesterday…. my thoughts changed.

While future generations may never know what a limited edition chapbook might be, I saw something that made me confident that, in one form or another, the fetishizing of the printed object will continue.

Yesterday, I took my son to Kids Tech University, an awesome program developed by Virginia Tech’s Bioinformatics Institute to spur youngsters’ interest in STEM disciplines (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). In the morning, a scientist spoke about her research in Antarctic core drilling samples. In the afternoon, the kids explored exhibits of various University-supported engineering projects.

An exhibit on 3-D Printing, a manufacturing process that can reproduce any physical object, caught my attention. I first read about 3-D Printing last year in a New York Times article. Last month, I heard again about it through an NPR Talk of the Nation story, but seeing the exhibit astounded me.

As the Times wrote,

“A 3-D printer, which has nothing to do with paper printers, creates an object by stacking one layer of material — typically plastic or metal — on top of another, much the same way a pastry chef makes baklava with sheets of phyllo dough.”

Digital pictures are taken of an object, which are then computer-processed, building up a digital record of the object’s dimensionality. The objects, which can be comprised of many components (including moving parts) are then “printed out” by spraying layer after layer of materials upon each other, allowing for each layer to dry before another is applied. The objects exhibited this weekend were made from rubber and resins, but other materials, like copper and concrete, can be used. To print out a fully-functioning adjustable wrench might take several hours but it’s amazing that objects which used to be hand-forged or assembled from molded parts can now be manufactured more effortlessly with much greater precision.

Although I didn’t ask, my guess is that the process needn’t begin with the photographing of an actual object. Instead, one could probably design the objects through computer animated designs.

One of the exhibitors said that the images can even begin as CT scans, allowing surgeons the ability to print-out a patient’s body organs to get a better idea, say, where malignant tumors may reside.

As the technology progresses, I wonder if fully-bound books might be printed out this way. Theoretically, 3-D Printing might actually expand book culture’s fetishizing of the printed object, allowing for the custom printing of newer, more fantastical books.

The other day, in my post about The Official Catalogue of the Library of Potential Literature, I quoted the Adam Robinson’s idea of a “wooden novel” composed of different “drawers.” Today, such a thing might not be possible. However, through 3-D Printing, it’s conceivable that such a book might yet be made, allowing readers new ways to immerse themselves in the printed word. Meaning, the technology behind the printed book need not be dead.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed