Yes, I understand the skepticism. As writers, we’ve been trained to mind-numbingly nod our heads at the feel-good platitudes about the worth of our work. We instinctively clap upon hearing for the billionth time Shelley’s line about “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” And we even cheer for despicable Ezra Loomis Pound’s “Literature is news that stays news.”

But who are we kidding? However, um, elegant Harry Reid and John Boehner may be, my hunch is that neither can write so much as a limerick. If literature is “news,” how come it receives such scant attention?

In this case though, I believe Hessel is right if what is being created is not the same as everything else that’s already been created.

I’m not one of those people who believe literature has to be proscriptive or even directly address sociopolitical issues. But I think it ought to attempt to pose questions and scenarios that haven’t been posed before. Innovative & imaginative forms can be the best means to voice our unease or indignation. But you know this. Just as contemporary installation art is capable of saying different things than classical marble sculpture, innovative literature can provoke different responses than traditional realism.

So why is innovative literature so disparaged in the marketplace? Probably because there’s not enough of it.

I’ve been thinking about “Defining Deviancy Down,” the Daniel Patrick Moynihan essay first published in 1993. Moynihan, an aide to four presidents and a four-term New York senator, was something of an intellectual in his day. Putting aside his troubling use of “deviancy,” the essay is illuminating.

Moynihan posited that society’s tolerance for criminal acts is relative. In times of high crime, lesser criminal acts will be tolerated or even be deemed to be “normal.” If the land was overrun by serial killers, we’d suddenly become a lot less fussy about prosecuting petty larceny so that we could concentrate our attentions on those serial killers.

In this circumstance, Moynihan writes, “society will choose not to notice behavior that would be otherwise controlled, or disapproved, or even punished.”

In other words, it’s the behavioral outliers that dictate our societal norms.

I wonder if the same idea could help explain society’s tolerance for artistic innovation and prevailing aesthetics. Could aesthetics be dictated by the extremes?

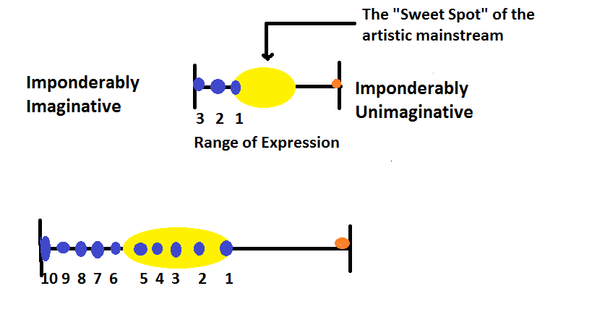

Permit me the following illustration:

In that first line, the “3” dot represents the extreme of available “imponderably imaginative” works. Because it lays at the extreme, my guess is that it will pass totally unnoticed by mainstream culture.

Now imagine the second line. Here, the bounds of imaginative literature are pushed even further. While there may be more net imaginative works (dots 6-10) that are banished or ghettoized outside of the mainstream, their mere existence increases society’s tolerance for imaginative literature. Works that otherwise would have been outside the mainstream (dots 2 & 3) are now within the mainstream—hugging the most conservative border of that mainstream.

To use a Gladwellian term, this is how imaginative literature can reach its “tipping point.”

Will it work overnight? No. But can it work? Maybe.

Over 200,000 copies of Donald Barthelme’s SNOW WHITE were in print within its first year of publication. Barthelme’s novel is an incredibly innovative work and, at times, incredibly challenging. If it were published today, it would probably pass unnoticed. So why was it such a success?

My guess is that back then, publishers must also have been putting out a lot of books that were even more innovative than Barthelme’s—so many so that SNOW WHITE wasn’t seen as being extreme (or, to borrow Moynihan’s term, “deviant”) but “normal.”

[Political aside: I’ve always wondered why conservatives are so eager to nominate candidates for major offices who, to my tastes, seem so “extreme.”

Now I think I know: people like Sarah Palin are necessary because they allow the John Boehners and Mitch McConnells of their ilk to appear positively “normal.” They’ve broadened the political marketplace. Politicians who twenty years ago would have been seen as too conservative to be viable candidates have been mainstreamed.]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed