Ever since picking up a copy of Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago as a teen, Ell had been fascinated by tales of Soviet gulags. I can understand this fascination: terror and misery, as a subject matter, have a hold on us.

Yet there's this wonderfully reflective moment in the article where Ell begins to question what, exactly, he was hoping to find in that quarry.

"I don't know what I was expecting to find there. Solzhenitsyn's mitten? An inkwell of suffering so deep that I would be able to dip in my pen and write words that would make readers weep?"

I understand his feelings, and his frustrations. We seek out sites of disasters, memorials and museums dedicated to genocides and terror and tragedy. We go to lectures, watch movies and television documentaries about the great horrors of our time-- the Holocaust, the Rwandan genocide, the Bataan Death March, Ground Zero and the World Trade Center bombings. But to what end?

Surely, there’s the need to remember the fallen. And, yes, there’s the Santayana adage that tells us “those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.”

But the impulse runs deeper than that—there’s the need to affirm our own humanity. Confronted with tragedy, we need to remind ourselves how precious life is. This is hardly an original thought, but it’s true. As is the realization that random chance plays a great role in our present survival. Each of us exists today because our forefathers and foremothers did not fall prey or be eradicated by some earlier genocidal impulse.

The other great fear each of us confronts when remembering the dead is that, given a little prodding, we might not be unlike those who perpetrated past crimes.

There’s a great United States Holocaust Memorial Museum video about “Why We Remember the Holocaust” that reminds us that the Holocaust was abetted and enabled by “so many people who participated in different ways, who made it possible: people who followed orders without questions; bystanders who watch and do nothing; ordinary men and women simply going with the flow.”

Remembering, as the video suggests, “is a call of conscience today in our world to make sure we aren’t the silent ones standing by and contributing to the suffering of others.”

Returning to Ell’s great reflection. When I first read it (“an inkwell of suffering so deep”), I immediately thought of its great converse:

In “Tombstone Blues,” Bob Dylan sardonically sang

“Now I wish I could write you a melody so plain

That could hold you dear lady from going insane

That could ease you and cool you and cease the pain

Of your useless and pointless knowledge”

“An inkwell of suffering so deep” versus a “melody so plain.”

A melody so plain that could numb you and narcotize you and cause you to stop thinking, stop feeling.

It’s no accident that the Nazis sought to ban modern art from museums and art galleries and replace it with propagandized depictions of Aryan heroics and inoffensive, dulled-down and idealized landscapes that provoked no serious questions or emotions. An art that doesn’t questions its culture is scarcely art—it’s wallpaper. And a people that fail to interrogate the wisdom of its leaders is, as history proves, easily manipulated into committing great horrors.

At its minimum, challenging art teaches that multiple valid ways exist in which to view the world. When you step into a gallery and are confronted with paintings you can’t readily interpret or understand, you realize very quickly that other people (for example, the artist who painted that indecipherable painting) think very differently from you. In other words, art teaches tolerance.

Of course, at its best, art challenges your assumptions about the world.

Return back to that “inkwell of suffering,” which brings us closer to our fellow man. By remembering his or her suffering, we actively contemplate three points-of-view: the victim, the perpetrator, and the bystander. We become part of the tragedy just by thinking about it. And we become part of the anti-tragedy as well when we contemplate how things might have—should have—been different.

Not all dramas take place on the stage, or even in the physical world. For most of us, the most riveting dramas we see are played out solely within our mind. Remembrances, with their implicit multi-faceted perspectives, become, if you will, a form of art.

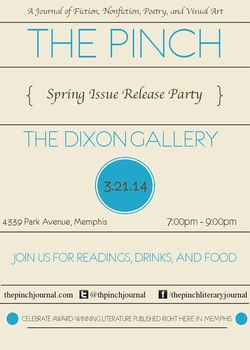

Errata: I’ll be reading tomorrow night (March 21) in Memphis to celebrate the release of the new issue of The Pinch. The event begins at 7 pm and is being held at The Dixon Gallery, which seems like a gorgeous venue. If you’re in the area, do drop by!

Errata #2: I’ve done a fair bit of reviewing lately. Here’s a Heavy Feather Review review I wrote of Jessica Hollander’s IN THESE TIMES THE HOME IS A TIRED PLACE, which won the 2013 Katherine Anne Porter Prize. Within the next few weeks, I should also have reviews up at Necessary Fiction, The Collagist, and another at Heavy Feather Review.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed