As the sessions start, the new material (including hits like “Get Back,” “Let It Be,” and “The Long and Winding Road”) is in very rough shape. Many of the filmed performances are, at best, rudimentary. In one excruciatingly painful sequence, Paul McCartney calls out the chord changes to his band mates as they slog through perhaps their first pass at “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.”

To say the band lacked enthusiasm would be an understatement.

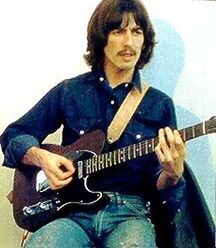

I’ve seen the film several times and have listened to countless hours of bootleg audio recordings from these sessions. Last night, watching it again, I was struck by how incredibly brave it was for the band to reveal their collaborative process. At times, the band appears disinterested in each other’s songs. During one heated moment, Paul McCartney rejects George Harrison’s suggestions for the lead guitar part on “Two of Us.” The brow-beaten Harrison ends up telling the domineering McCartney that he’ll play Paul’s songs however Paul damn well wants them to be played.

Although not depicted in the film, Harrison briefly quit the band during these sessions. Upon hearing Harrison’s announcement, John Lennon immediately suggested that Eric Clapton become his replacement.

Still, there are brighter moments, including this bit documenting the creation of “Octopus’s Garden.” Ringo Starr (piano), Harrison (guitar), and Lennon (drums) goof around with the nascent song, which was ostensibly written by Starr. Harrison takes over at the piano to provide ideas on how the song might be developed— lending the kind of generous suggestions that McCartney probably would not have countenanced.

Literary collaborations are far less common than musical collaborations, yet they can be just as messy. A few years ago, Julianna Baggott and Steve Almond wrote an epistolary novel together, WHICH BRINGS ME TO YOU.

Almond, in a Poets & Writers interview, said that “the collaborative process was more than we had banked on. As in: a lot more.”

He and Baggott argued a lot. Neither were particularly careful about each other’s feelings. Although they ended up with a published novel, the subtext of this article (and Baggott’s interviews) makes me wonder if it was worth it. What had been a friendship seems to have fractured.

Collaborations have been much on my mind lately. Earlier this year, “The Boy and The Palm Reader,” a story I wrote with Jenniey Tallman was published in The Collagist. As we said in an interview, the process was phenomenal. We had none of the arguments that Almond & Baggott experienced, and—to the best of my knowledge—neither of us sought to have the other replaced by Eric Clapton.

Last week, another friend asked me to help write some poems with him. I’m very much looking forward to the process. Mind you, I’ve yet to send over my revision suggestions, which is when conflicts might arise. He’s a far better poet than me and it’s possible that all my eventual suggestions will be rejected. Still, I’m looking forward to seeing something gel together that neither of us could have created if left to our devices.

Lately, I’ve been searching for good pieces of collaborative literature. Here’s “Bone Letters,” by Nicelle Davis and Peter Schwartz. And here’s “360,” a poem written by Kevin McLellan and Steven DeMaio.

“The Fan Dancers,” written by Molly Gaudry and Lily Hoang, is one of the best collaborative pieces I’ve read. At times sparse, at times lush, this amalgamation of poetry and prose startles. The jarring styles and images are nothing short of magical.

Although Gaudry and Hoang touched on their collaborative process in their PANK interview, I asked them a few more questions via email and they were gracious to respond

Why collaborate?

Two heads are better than one? Or because Molly’s head is better than Lily’s, or Lily’s head is better than Molly’s, or because Lily has always wanted to be one half of a conjoined twin and it matters not what Molly wants.

What are the risks in collaboration?

One head might not like what the other head is doing. One head might move at a slower pace than the other head. One head might be brilliant and the other head might feel like a slug. The head that feels like a slug inevitably discharges liquid, which is gross and smells terrible, but these are the risks the brilliant head must out-maneuver.

Why are there so few collaborative pieces?

Oh, no. I think the definition of collaboration is too strict here. A book is a collaboration between the author, the publisher, the editor, the designer, and the list goes on. Movies are collaborations; theatre performances are collaborations; orchestral symphonies are collaborations. But if we’re talking about literature, about two or more authors coming together to make words, then I imagine the possible reasons are those that were mentioned above, in the answer to the “risks” question. Writers like to believe in originality, genius, self-aggrandized brilliance, all of which lead to depression. Better to collaborate and be happy, if you ask me.

Guadry and Hoang’s playful answers made me laugh.

Look again at that “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” video. I defy you to tell me that those four slugs (five, if you count roadie Mal Evans, who’s pounding the anvil) aren’t discharging something gross and terrible.

I also totally get what Guadry and Hoang say about writers clinging to the belief of “originality, genius, [and] self-aggrandized brilliance.” While we all hope to claim those traits, they trap us, making us resistant to the influence of others. To enter into collaboration can be a de facto admission that, well, maybe we need to latch onto another writer’s brilliance.

During those January 1969 rehearsals (though sadly not included in the LET IT BE FILM), George Harrison introduced his song, “Something,” to the other Beatles. Harrison was clearly influenced by James Taylor’s “Something in the Way She Moves,” which was released the previous year by The Beatles’ Apple Records.

Harrison’s song was far from complete during these rehearsals. Though the melody is fully formed, the opening lyrics were “Something in the way she moves / attracts me like a pomegranate.”

As ugly as some of the placeholder lyrics were, there’s a beautiful recording of his rehearsal that’s partially embedded in this video. What makes the recording beautiful is the loving care in which John Lennon is trying to help George write the song. Neither of these great songwriters are clinging to ideas of originality or self-aggrandizing brilliance. It’s nothing short of spectacular.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed